Introduction

Art in Europe between 1915-1930 has become a confusing and neglected art. Most works were tied with sociopolitical events of the time and so a contemporary viewer cannot easily understand the context and theory behind this art. This Blog-museum is dedicated to reintroducing this art to a contemporary viewer by immersing the viewer in the time period through a variety of mediums. As opposed to a museum, by using a blog, the visitor can selectively focus on the subject of his/her interest and the work can be presented in a more familiar and interactive format. Videos and audio are prominently displayed in a way that would not be possible in a museum, as often at a museum a viewer is not inclined to spend time waiting and playing with equipment. Also, it is distracting to have multiple videos and audios playing throughout the museum. Furthermore, the material is more accessible and can be viewed for free, at any point and from anywhere that the viewer wishes. There are a variety of links so a viewer can have the choice to learn more about things that only get mentioned on a piece’s label. Consequentially, we hope that this format will help to bring understanding to the subject of these works. Thus, we hope that by using modern means we will be able to recreate the past. All items of our blog belong to the collection of the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design. Some of these items have never been open to the public, so this blog also is used to introduce new material of the time period and provide new information about this period both for scholarly interest and public viewing.

Historical Context: The Age of Anxiety

World War I (1914-1918) drastically changed the political, cultural, and social order throughout Europe.

Click here to watch a short clip about the history of the First World War World War I Video

Click here to watch a short clip about the history of the First World War World War I Video

The realities of war left the continent physically, economically, and emotionally devastated. This was a great contrast to the "roaring twenties" of the United States. In the years following the war the collective consciousness of Europe was flooded with an overwhelming sense of crisis. This “Age of Anxiety” can be directly attribute to the economic crisis the plagued the inter-war years, as well as the numerous conflicts that arose between the establishment values and regimes that had lead to the destructive war, and the emerging revolutionary organizations and ideolgies.

In the years following World War I, Germany took to printing money to help meet expenses.

With inflation spiraling and the mark plummeting, things worsened when the French occupied Germany's Ruhr region.

Here, the Salvation Army serves hungry Berliners in the dark days of 1923.

The artistic movements that emerged in post-war period explored similar themes: abandon tradition, experiment with the unknown, changes the rules, dare to be different, innovate, and above all, expose the sham of western civilization, a civilization whose entire system of values was now perceived as one without justification.

Prints, Drawings & Photographs Department 1920’s-Present

Nearly seventy years after the RISD Museum was chartered in 1854, the museum had become home to many influential works of art. The 1920’s for RISD and other American museums was a golden age. During this time period with which this virtual museum begins, the museum was reaching a new level of growth. It was in 1929 when the Rhode Island school of design became a separate entity from the Museum, as both had become too large for one organization to run. The Museum’s first director, L. Earle Rowe (1882-1937) began his work there in 1912, and with the help of Eliza Metcalf Radeke helped the collection continue to flourish. Radeke became the president of RISD in 1913. It was her interest in a wide variety of art from Japanese textiles, to European paintings, drawings and sculpture. During the 1930’s a great deal of important nineteenth-century French works and a noteworthy collection of Napoleonic decorative arts and sculpture were added to the museum’s collection.

While the Great Depression and World War II took a strong effect on the institution, the advent of modernism caused an equally strong reaction. In this art school and museum, the Avant Guard forced a distinction between progressives and traditionalists. The change modernism caused was embodied in the work of the director Alexander Dorner (1893-1957). He was considered one of the most innovative museum directors in prewar Germany, and had been the director of the Landesmuseum in Hannover. Dorner had gained international recognition for his commissioning El Lissitzky to create “The Abstract Cabinet”(1927-1928), a gallery for avant-garde art with angled and mirrored walls.

Portrait of Alexander Dorner

Director of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1938-1941

By 1937, when the Nazi’s had declared art like this as ‘degenerate,’ Dorner had already left for the United States. With recommendations from celebrities in the American art scene, including Alfred H. Barr, Dorner was made the director of the RISD Museum in 1938. He introduced modern display techniques and audio equipment into the galleries. Also, he redid the Museum’s publications and design. He loved abstract painting, sculpture, modern architecture, and film. He was responsible for acquisitions such as Matisse’s Still-Life with Lemons ca. 1914 and Church at Gelmerode XII, 1929 and Franz Marc’s Two Horses 1912. Dorner’s other most enduring legacy was his vision of the Museum as a passage through time rather than an assortment of national schools of art. He combined different mediums of art and sensory experience in the galleries so they would unfold chronologically. He sought to reveal what he called “ the dynamism of culture” in a “living museum,” as an approach ideal for a teaching institution.

Dorner was succeeded during the war years and shortly afterward by a talented group of German and Austrian émigrés. In 1943 Dorner’s successor, Gordon Washburn appointed Austrian Heinrich Schwartz as curator of prints, drawings and paintings. His contributions to the RISD collection of prints and drawings and paintings ranged from old masters to Picasso. About fifty years later in 1984, a major gift of American prints, drawings, and photographs was given to the Museum by the Fazzano brothers of Providence.

The expansion of the collection beyond the capacity of the existing storage rooms and increased number of exhibitions and public programs, lead to the building of the new wings, including the Chase Center in 2008, which among other things is home to the Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs in the Chase Center at the RISD Museum

Movements of the Avant-Garde

DADA

Dada is the ground from which all art springs, Dada stands for art without sense. This does not mean nonsense. Dada is without a meaning, as Nature is.

-Hans Arp

Dada is the ground from which all art springs, Dada stands for art without sense. This does not mean nonsense. Dada is without a meaning, as Nature is.

-Hans Arp

Dada Soirée, Paris, 1920

Dada emerged during the height of World War I in direct response to the chaotic violence and mass slaughter that was enveloping Europe. Although it originated in Zurich, a place of relative neutrality during Word War I, the movement quickly spread through Europe, most notably in Zurich, Berlin, and Paris. While Dada activities varied from city to city, from the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich to the publication of numerous journals in Paris, each faction remained united in their desire to create works of art, literature, and performance that reflected the rapidly changing conditions of modern life.

Despite its status as a pioneering movement of the Avant Garde, Dada defied all previous understanding of a unified artistic style. Dada lacked collective standards of formal characteristics, media, methods, and exhibition practices. They were a movement defined by singularity, by an express desire to present a unique vision of the individual’s experience of the surrounding world. As a result of their refusal to conform to any notion of artistic expression besides their own, the Dada movement was imbued in contradictions and mystery.

Today, the inherent complexities of the Dada movement continue to astound and affront scholars and museum goers alike. Removed from its historical context, Dada has become a movement defined by its peculiarity, achieving an almost mythic status. Therefore, to fully appreciate the impact of Dada, it is necessary to return to the social conditions from which the movement emerged.

The Battle of Verdun 1916

The often destructive and anti-war practices of Dada can be directly linked to the events of World War I. Many artists who joined the movement, including Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Alfred Jarry, and Louis Aragon, had been drafted for military service and witnessed the atrocities of war first hand. Their battlefield experiences had a profound impact on their social and cultural views in the post-war years, as is particularly clear in works like Otto Dix's Prager Street. While the rest of Europe attempted to rebuild what war had destroyed, soldier's returned from the front lines to an unfamiliar, violent, and ugly world. For some artists, a growing sense of displacement engendered unshakable feelings of contempt towards the institutions and political ideologies that lead the war. As they believed traditional artistic methods and styles lacked the potency to express the new world order, Dada was born.

ON RIGHT: Bodies left in a trench in France , ON LEFT: Otto Dix, Prager Street

SURREALISM

SURREALISM, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express, verbally, in writing, or by other means, the real process of thought. Thought's dictation, in the absence of all control exercised by the reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.

ENCYCLOPAEDIA. Philosophy. Surrealism rests in the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association neglected heretofore; in the omnipotence of the dream and in the disinterested play of thought. It tends definitely to do away with all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in the solution of the principal problems of life. Have professed ABSOLUTE SURREALISM: Messrs. Aragon, Baron, Boiffard, Breton, Carrive, Crevel, Delteil, Desnos, Eluard, Gérard, Limbour, Malkine, Morise, Naville, Noll, Péret, Picon, Soupault, Vitrac.

-André Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924

The International Exhibition of Surrealism, New Burlington Galleries, London, 1936

Front Row: Paul and Nusch Eluard, E.L.T. Mesens, Salvador Dali is in the Diving suit

Surrealism emerged in the late 1910s and early '20s in response to the growing artistic and ideological tensions of the Dada movement. The Surrealists rejected the seemingly destructive and anarchistic attitudes Dada, embracing constructive artistic production that relied on subconscious intervention and experiments. In its formative years, Surrealism focused on the use of literary form as means of political and social protest and personal exploration, publishing countless manifestos, periodicals, and journals, including the 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, by André Breton. Drawing heavily on theories adapted from Sigmund Freud, the Surrealist viewed the unconscious as a wellspring of imagination. Through a variety of writing exercises and city wanderings, the Surrealists attempted to gain access to this normally untapped realm, which, they believed, would allow pure artistic expression.

In addition to these experimental literary forms, the Surrealists also employed more tradition media in their search to define a new aesthetic and social order. By exploiting the inherent characteristics of traditional materials, such as paint, metal, and the photograph, the Surrealists engaged in protest against the normative values of society, and the art world, by occupying the very space they sought to reject. Through this direct engagement with mainstream society, the Surrealists were able to challenge form, composition and style before a much broader audience than their Avant Garde predecessors.

First Manifest of Surrealism, André Breton (1924)-FULL TEXT

First Manifest of Surrealism, André Breton (1924)-FULL TEXT

The Exhibition

MAX ERNST

German (1891-1975)

Untitled Frottage

Ca.1925

54.123

Like many Surrealists, Max Ernst was always experimenting with new artistic techniques. In 1925 he invented frottage and produced works such as this one. From the French verb frotter , ‘to rub,’ this method involves rubbings of objects as source images. The artist takes a pencil or some sort of writing tool and makes a ‘rubbing’ over the textured surface of an object. The drawing can be left as is, or often could be refined into a different image. This is like brass rubbing, but it differs in being a allegorical and random in nature.

Ernst was inspired to create this technique by an ancient wooden floor from which the grain of the planks had been accentuated by years of scrubbing. He said the grains suggested strange images to him. He then captured this images by laying paper on the floor and rubbing it with a soft pencil.

This was one of the ‘automatic’ artistic methods of the surrealists. These automated processes often lead to works like ‘Untitled Frottage,’ which are of nothing known in real life. This work definitely appears to be some sort of monstrous easel. The image on the ‘easel’ appears to look a bit like leaves, or trees, possibly with berries or people walking on it. The nature of the image is ambiguous and enthralling.

The Process of Frottage

KATHE KOLLWITZ

German, (1867-1945)

Unemployed, 1925

Brush and black ink with gouache on grey paper 18 ¾ x 14 in.

Mary B. Jackson

Käthe Kollwitz is one of the few and most famous female artists of this period. She was a German painter, printmaker and sculptor. Her works, in particular her graphic works including drawing, etching and lithography and wood cut express her empathy for the less fortunate and exposed the problems of poverty, hunger and war.

Kollwitz was a socialist and a pacifist and eventually communist. Her works exposed the devastation of post World War I Germany. The trauma and pain of war was a subject very close to her as she lost her son in World War I and her grandson in World War II. Her War woodcut print cycle frm 1922-1923 and the posters from 1924German’s Children are Starving, Bread, and Never Again War are some of Kollwitz’s best-known works.

In Unemployment Kollwitz shows an image of great depth of emotion and drama of the human relationships. The image is neither sentimental nor abstract. She uses heavy line work and dark shadows to separate the father figure from the rest of the family. The shadow work also gives the viewer a sense of being intimately close to these individuals and their suffering. The work shows a great use of variation in thickness of lines, etching and shadowing to create a dramatic interplay of light to focus the viewer on the facial features and emotions. The scene is as dramatic as the lighting and the dark tones give the work sense of despair. The artwork is symbolic of the social problems of this period in Germany’s history.

Click here to access more information about the difficulties of life for the average person in post World War I Germany.

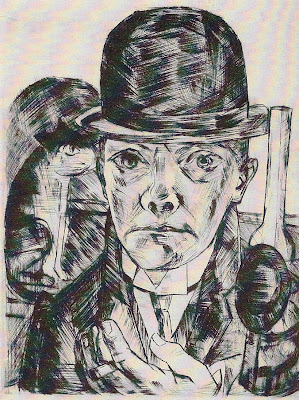

MAX BECKMANN

German, (1884-1950)

Self-Portrait with Bowler Hat, 1921

Drypoint plate 12 ⅝ x 9 ⅝ in.

Gift of Murray S. Danforth Jr. 51.511

Beckmann was a German painter, draftsman, printmaker sculptor and writer. While he was considered part of the Expressionist movement, Beckmann was never comfortable with this and in the 1920’s became associated with a group known as Neue Sachlichkeit, New Objectivity. Click here to learn more about the Neue Sachlichkeit movement.

Beckmann believed that artists were magicians and performers and in Self-Portrait with Bowler Hat he presents himself in the guise of a gentleman. Beckmann produced a significant amount of self-portraits that even rivaled the amount made by artists like Rembrandt. Beckmann had traumatic experiences during World War I, when he served as a medic. This lead to a dramatic change in his style from academically ‘correct’ depictions to a distortion of figure and space, which reflected his altered view of himself and humanity. Encompassing portraiture, landscape, still life, mythology and the fantastic, the work created a very personal vision of modernism.

Despite his initial popularity, Beckmann’s fortunes changed as Adolf Hitler came to power and began to suppress modern art. In 1933, the Nazi government called Beckmann a "cultural Bolshevik" and dismissed him from his teaching position at the Art School in Frankfurt. In 1937 more than 500 of his works were confiscated from German museums, and several of these works were put on display in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. Beckmann spent the next ten years in a self-imposed exile in Amsterdam trying unsuccessfully to get a U.S. visa because the German army was still trying to draft him, despite being sixty years old and having a sever heart condition. After the war Beckmann finally was able to move to the United States where he remained until his death in 1950.

Watch a video of the Degenerate Art Exhibition

Learn more about the Degenerate Art Exhibition, and view works displayed there

Learn about Hitler's Art and National Socialist Era Art

Image of Hitler at the Museum

PAUL KLEE

(German/Swiss 1897-1940)

Paul Klee was an important German/Swiss abstract artist. He was born in Berne, Switzerland in 1876 into a family of musicians. Music became an essential part of his art and became evident in his paintings. Klee is remembered as a versatile artist who was influenced by movements such as surrealism, cubism and expressionism. Most of his first works were done in pencil and ink, which he later replaced for colour. In his early years he traveled widely to locations such as Italy and Tunisia which were vital for his artistic development. Up to 1918, all of his impressions, thoughts and experiences of these travels were recorded in diaries, that still survive today. The diaries are an extraordinary source of information for understanding his paintings, which are steeped in art, music and literature. He continued writing throughout his life and all of his works are considered extremely important for art development and color theory. In these early travels he also met many artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. In 1906 Klee married pianist Lily Stumpf and moved to Munich. In 1920 Klee was invited to teach at the Bauhaus in Weimar. The Bauhaus was a school in Germany that attempted to close the gap between Fine Art and crafts. However, in 1932 the Nazis began rejecting this school and used propaganda to turn people against it both in the newspapers and then the School itself. After one year the school was closed and Klee was forced to leave Germany, returning to Berne with his wife Lily. This development greatly affected the artist and he mentally and physically weakened. He was diagnosed with sclerodermia, a disease attacking the skin, limbs and digestive system. The final years of his life, stigmatized with tragic global events and with his diseased introduce a new focus and artistic development for Klee. He died on June 29, 1940, in Muralto-Locarno.

This small print depicts an elephant and a lion. This attests to the multiple travels that Klee made during his life-time. We can assume that these two animals were either drawn while in Africa or where a memory from those travel. Klee enjoyed working with various media and combining them all in one piece. In this case, we see him experiment with a water-colour background and pen. The form these animals take are peculiar and unusual. They appear to be part of both a dream and a reality. Klee was indeed very interested in dreamlike images that often were inspired by his passion for music and its un-graspable nature.

Paul Klee in his Studio

René Magritte

(Belgian 1898-1967)

"the art of putting colors side by side in such a way that their real aspect is effaced, so that familiar objects—the sky, people, trees, mountains, furniture, the stars, solid structures, graffiti—become united in a single poetically disciplined image. The poetry of this image dispenses with any symbolic significance, old or new.” -Rene Magritte

"the art of putting colors side by side in such a way that their real aspect is effaced, so that familiar objects—the sky, people, trees, mountains, furniture, the stars, solid structures, graffiti—become united in a single poetically disciplined image. The poetry of this image dispenses with any symbolic significance, old or new.” -Rene Magritte

Paysage au Baucis

Soft ground etching with engraving and dry paint

René François Ghislain Magritte, was a famous Belgian Surrealist. He developed his signature techniques early in his career while working as a commercial artist-designing wallpapers, posters, sheet-music covers and collage illustrations. In August 1927, Magritte moved Paris and joined the Parisian Surrealists. There he experienced a great career bloom during which he would produce sixty pictures in one year, some quite large. However, he left Paris unsatisfied in 1930, since he believed that painters tended to be subordinate to the writers, and in particular to André Breton. He returned to Brussels where he was regarded as the center of the avant-garde circle. He remained in Belium, save for a few trips, until his death.

Magritte’s works were characterized with enigmas and peculiarities. He enjoyed juxtaposing everyday objects with a peculiar environment and so creating new narratives for these objects. Like the rest of the surrealists he hoped to “create something more real than reality itself”. As opposed to many other surrealists, his paintings exclude symbols and myths; everything is visible. He hoped that his works would be not over analyzed but simply taken in by the viewer. He believed that over-analyzing an image, resulted to stop “looking at the image itself, but instead thinking of the questions it raised”. In this sketch we have a picture of a man in a suit and hat, with no face except for his eyes, nose and mouth. A faceless man with a suit and hat became one of Magritte’s recurring themes. In the case of this print, we see him still experimenting with other facial features, which he eventually decided to hide (usually with a green apple).

(Spanish, 1881-1973)

Although a native of Spain, Picasso worked intermittently in Spain and France until 1904, when he settled in Paris. During his time in time in Paris, Picasso lived among many of the Surrealist artists in the quartier Bateau-Lavoir . By the end of the 1920s, his work had shifted away from the abstraction of Cubism, and instead began incorporating imagery and techniques of Surrealism.

Seated Woman (from the book Contrée by Robert Desnos)

Etching, 1943

The above etching, entitled Seated Woman, was created by Picasso to accompany Robert Desnos’s, 1944 poetry collection, Contrée. The dual depictions of a single woman, as well as the use of minimal linear compositions to create volume, evidence the Cubist roots of Picasso’s artistic style.

English Translation of Contrée The above etching, entitled Seated Woman, was created by Picasso to accompany Robert Desnos’s, 1944 poetry collection, Contrée. The dual depictions of a single woman, as well as the use of minimal linear compositions to create volume, evidence the Cubist roots of Picasso’s artistic style.

Pablo Picasso with his work

Joan Miró

(Spanish-Catalan, 1893-1983)

Color Lithograph

1905

Joan Miro was a Spanish surrealist painter. He was the son of a goldsmith and jewelry maker in Barcelona in Northern Spain. He studied arts at the Barcelona School of Fine Arts and at the Academia Gali. In the beginnings of his career he experimented with different popular painting styles such as Fauvism and Cubism. He earned international acclaim as a surrealist artist.

His art was characterized by childlike drawings that emerged from the subconscious mind. He was one of the first artists who developed a new artistic style- automatic drawing. Even though his art and beliefs was very similar to surreal ideals, he never officially became a member of the group.

The print at the Risd museum exemplifies his child-like yearning. In the print there are some recognizable forms such as the moon, however it is not clear what the main figure is. The automatic drawing is also present. In theory this style depended on the hand moving randomly across the paper, guided from the unconscious. We can see some of the signs of this new style by the figure and around the border.

Portrait of Joan Miró,

Paris, 1933

Photograph : Man Ray